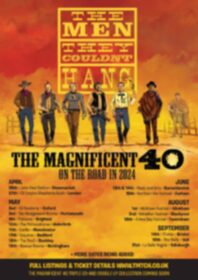

News: The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing Announce New Album And Tour

on February 10th, 2018 at 21:15Including A Date The Joiners In Southampton

“I’ve always preferred “Victorian-themed punk rock”,” says Andy Heintz, charismatic pink-bearded frontman with The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing, when asked to give a name to the band’s genre. Andrew O’Neill, guitarist/vocalist and co-founder, pauses for a second then grabs the perfect self-description out of the ether. “Anachro-Punk!”

Formed ten years ago, but with hearts rooted firmly in 1888, The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing (the name, of course, derives from a chalk inscription found in Whitechapel near the bloodied apron of Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes) are a band who have been closely associated with the Steampunk subculture.

The band always had mixed feelings about the S-word, as signalled by their sardonically-titled debut album Now That’s What I Call Steampunk Vol.1 (later renamed The Steampunk Album That Cannot Be Named For Legal Reasons after a cease-and-desist warning from EMI, owners of the Now! Series). A decade later, when Steampunk subculture is so far overground that you can buy whole outfits off the peg in fancy dress shops, The Men are happy to move beyond the label. “A couple of years ago,” says O’Neill, “I put out a zine called Fuck Steampunk, which started “Hello, cunts! So, Steampunk’s pretty shit now, isn’t it?” My personal vision of what Steampunk could have been was this anarchist future-dystopian skill-sharing thing. Let’s learn how to make stuff, let’s learn how to fix stuff. There’s a great book about this called The Steampunk Guide To The Apocalypse. But what it became was people dressing up at weekends.”

As bassist/vocalist Marc Burrows points out, one crucial difference lies in the content of The Men’s work. “Steampunk has a cyberpunk element to it that we never had. Our songs are set in a realistic 19th century. A grimy dark underbelly of Victorian London which actually existed.” O’Neill agrees: “We’re Peter Ackroyd, rather than William Gibson.” So, with one foot inside the Steampunk camp, and one foot out, are they The Men That Doth Protest Too Much? “We like a lot of Steampunks but we don’t feel part of it, O’Neill explains, “We’re not in denial, like the “I’m not a goth” thing, but we don’t think it’s a good fit for who we are as four different people.”

Those four people were originally two. Andrew and Andy met at UCL students’ union, when O’Neill was working in the shop and Heintz was helping with a refurb. They bonded over an exchange of music: the former would be listening to metal, and the latter would throw Digital Hardcore albums at him. Both had been in bands: Heintz as leader of London goth-punk cult heroes Creaming Jesus, and O’Neill in a long list including SunStarvedDay and Plague Of Zoltan (who he remembers as ìextreme chaotic hardcore/grindcore kind of stuffî). O’Neill’s musical ambitions were on hold while his successful stand-up comedy career was just beginning to take off. This, ironically, gave birth to The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing. When Andrew toured a show called Andrew O’Neill’s Totally Spot-On History of British Industry, he brought Heintz on board to help write and perform some daft songs and play musical saw. ìIt was wildly unpopular,” O’Neill remembers. “We played Northampton and the DJ cut our sound,” Heintz confirms. “He actually started playing ska records over the top of us.”

Marc Burrows, also a comedian and writer, first met O’Neill at the Edinburgh Fringe, where they’d bonded over Wayne’s World quotes and a shared sense of humour. He came on board on bass for the British Industry show at the Cockpit Theatre near Baker Street, (having previously been a member of punk band The Pittstops and a “sub-Radiohead” indie band called Threadbear). With the addition of drummer Ben Dawson, best known as a member of Million Dead with Frank Turner (and a former bandmate of O’Neill’s in SunStarvedDay), the first line-up of the quartet was complete. They began with a 25-minute set, having rehearsed for the first time on the same day. O’Neill remembers it as a lightbulb moment: “I knew this has to be what we do from this point.”

Dawson hung up his drumsticks in early 2010, after completing recording of the debut album (“he REALLY hated Steampunk” says Burrows), and was replaced by multi-instrumentalist Jez Miller, formerly of Lords Of The New Church and Britpop band Showgirls. The classic line-up of The Men has remained the same ever since. Burrows believes Miller helped define the band’s sound. “Jez plays drums with this lovely Glam Rock swing and character, and the sound of the band is the tension between that and Andrew’s more hard-edged guitar style, with my bass bridging the gap.”

Having two comedians in the band does, they admit, raise certain troublesome preconceptions. “I hate the word “novelty” or “comedy”, says Heintz, but…”, O’Neill finishes his sentence: “We were basically a comedy act when we started.” They cite Chas’n’Dave and Ian Dury, both known for lacing their songwriting with humour, as influences. The ribald comedy of Victorian music hall, too, is an obvious influence. They’re wary, however, of being seen purely as gag merchants.

“Double Negative”, the band’s fourth studio album, is a powerful corrective to any such myths. It’s mordantly, viciously funny, but also exudes a righteous fury about social and political wrongs in the not-so-distant past (and, one senses, the present). As with any period or historical art, the question always arises: is it actually about what’s happening now? “You don’t have to look very hard to find those parallels of injustice,” Burrows admits. O’Neill has a theory about this: “I think of it like a Rorschach Dot. You do something about the past, and people say “Ah, well that’s about Brexit…” The Victorian age is a prism to view today through. We’re living in the system that the Victorians built.”

Musically, Double Negative is arguably the band’s least “steam”, and most “punk” album yet. “As we’ve navigated through our albums,” O’Neill explains, “we’ve been less and less concerned with Steampunk, and less and less concerned with Victoriana, and more and more bothered with what sounds do we want to make? It’s much more hardcore punk than ’77 punk. It’s heavier, and less obviously funny.” Burrows calls it “a streamlined, angry, short record” which “starts off as straightforward hardcore meets New Wave Of British Heavy Metal”, but “gets weirder as it goes along”. Big Black, Swans, Refused, Gang Of Four and Slayer are all mentioned as having informed its sound.

The intent behind this shift in emphasis, reckons O’Neill, was as much political as musical. “We wanted to make a short sharp angry punk album. Because we’re four different stripes of Leftist, from Jez who’s the most state socialist and I’m an anarchist, and the other two guys are somewhere in between. And we’re all fucked off with Brexit, and Trump, and racists thinking it’s alright again. And it needs this cathartic expression. Particularly within Steampunk, where there’s a lot of reactionary conservatism – the British Empire and people pretending to be toffs, and a lot of militarism. Steampunk’s pretty Brexit. And someone needs to address that.”

Heintz addresses these issues and more in his lyrics. Every song may be about the Victorian age, but there isn’t the slightest drop of rose-tinted nostalgia. These are true stories, almost unremittingly grim and grisly in nature. “Supply And Demand” is about the grisly body-harvesting of Burke & Hare, ìBaby Farmerî about Amelia Dyer, the purported foster parent who actually drowned unwanted babies in the Thames, and ìGod Is In The Bottom Lineî deals with the horrors of child labour. All three can be read as allegories for the rapaciousness of modern capitalism. “They’re all about economics,” agrees Heintz. “I wrote them about that time, but when I thought about it, actually nothing’s bloody changed…”

A similar thing could be said about “Occam’s Razor”, which is – perhaps surprisingly – the first time The Men have written a song about Jack The Ripper. “And it’s not really about Jack The Ripper,” says Heintz. “I did a show called Winston Churchill Is Jack The Ripperî, O’Neill adds, ìwhich proved it beyond reasonable doubt. Because obviously it ‘has’ to be someone famous, if you believe all these books. The whole Ripper industry is fucking disgusting.”

“Hidden”, though written by Heintz, touches upon one of O’Neill’s obsessions, namely magick. (Andrew performs a rite called The Bornless Ritual during the song.) “Obscene Fucking Machine” deals with the depravity of Queen Victoria’s grotesquely overweight son Prince Bertie, who had a special chair made which supported his bulk while enabling him to have sex with two people at once, and whose son was rumoured to be embroiled in the Cleveland Street Scandal involving child prostitutes. In fact, the only entirely fictional song on the album is “There’s Going To Be A Revolution”, an uncharacteristically impassioned ending, warning of an uprising that would ultimately never materialise. ìWe should have called it ‘The Revolution Predates The Existence Of Television’,” says O’Neill. “We missed a trick there…”

In an era when our politicians urge us to ignore the views of “so-called experts”, it seems quite significant that there are two songs in which the heroes are scientists. “Disease Control” hails John Snow’s discovery that the Soho cholera epidemic of 1854 was waterborne, while “There She Glows” is a love song to Marie Curie, whose pioneering experiments with radiation led to her death from aplastic anaemia. ìHer actual recipe book is still radioactive,” says Burrows. “You have to handle it with special gloves.” O’Neill, never off-duty, spots a low-hanging punchline: ìthere are no microwave recipes in it.”

Indeed, Double Negative is an album that might never have happened, were it not for the intervention of 21st century medical science. In 2014, Andy Heintz was diagnosed with throat cancer. At first, he’d refused to make a fuss about the growth. “I was in denial. I thought it was a blocked lymph node.” But even his bandmates had noticed. “He had a visible lump in his neck, and he was like “Ah, I’ll be alright!'”, recalls O’Neill. “His wife had to make him go to the doctors,” adds Burrows.

The day of the diagnosis the band came onstage as encore for one of O’Neill’s stand-up shows. The following day, treatment began, leaving an American tour in tatters, and obliging the remaining Men to soldier on without him for just one further show. But it wasn’t just any show. It was the Glastonbury Festival. “We went onstage as he was going into radiotherapy,” Burrows recalls. “Like, ‘I’m going in!”, “Well, we’re going on.” It was really horrible.” After six months of treatment (the band uploaded a video of his radiotherapy to YouTube), Heintz had no thoughts of retirement. He couldn’t wait to get back to singing. “The good thing was, I lost loads of weight. So it killed the cancer and got rid of Type 2 Diabetes. Not eating solids for six months is a remarkably effective cure. And my voice has a nice rasp to it now…”

Heintz’s comeback gig was at the Highbury Garage. ìI have never heard a noise from a crowd like the noise when Andy walked out onstage, remembers Burrows with goosebumps. “We milked it a bit: we wouldn’t let him leave the dressing room to watch the support bands so no-one could see him. People were wearing knitted pink beards like Andy’s.” With typical gallows humour, Heintz wore his suffering on his sleeve. Or, to be precise, his face. ìFor the encore, I put on my thermoplastic radiotherapy mask.”

The Men’s devoted fanbase are a diverse bunch. “People come to us in such different ways,” says O’Neill. “There are the Steampunks who come to us for the Victoriana, and because we bring something to that scene that it didn’t have. There’s proper metal fans, punks, goths.” Heintz believes that the mix of comedy and seriousness is central to their appeal. ìWe temper the heaviness with the humour. There are people who put up with the humour because of the heaviness, and people who put up with the heaviness because of the humour.î

The two sides to The Men will be reflected not only on Double Negative, but on the next record after it. “We’re on a two-album cycle,” says O’Neill and any songs that are more expansive and epic will go on the next album, which will be a counterpoint to this.” Heintz elaborates: “I think of it as “urban and rural”. This is the town one, and the next one’s gonna be countrified. But not literally Country.”

The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing are, O’Neill believes, The Band That Have Found Their True Direction. “We’re finally turning into the band we would have been,” he says, shaking himself free from invisible Steampunk shackles.

Simon Price, Feb 2018

“Double Negative” is available on CD, Cassette, Vinyl and Digital Download with exclusive pre-order bundles now

The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing are:

Andrew O’neill: Guitars, Vocals

Gerhard ‘Andy’ Heintz: Vocals

Marc Burrows: Bass, Vocals

Jez Miller: Drums

The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing on tour:

MON 12 MAR – Nottingham, Rescue Rooms

TUE 13 MAR – Newcastle, Trillians

WED 14 MAR – Edinburgh, Bannermans

THU 15 MAR – Birmingham, Castle & Falcon

SAT 17 MAR – York, Fulford Arms

SUN 18 MAR – Milton Keynes, Craufurd Arms

MON 19 MAR – Cardiff, Globe

TUE 20 MAR – Chester, The Live Rooms

WED 21 MAR – Leicester, The Shed

THU 22 MAR – Exeter, The Cavern

FRI 23 MAR – London, The Dome

SAT 24 MAR – Southampton, Joiners

SUN 25 MAR – Bristol, The Exchange

Links

http://www.blamedfornothing.com

https://www.facebook.com/blamedfornothing

https://twitter.com/blamed4nothing

https://blamedfornothing.bandcamp.com